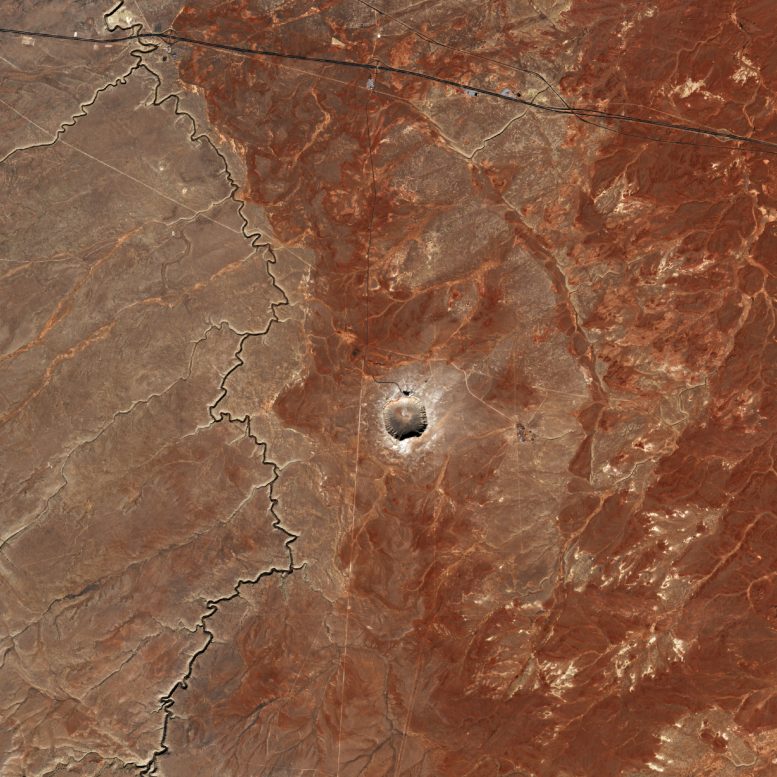

The Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission reveals the Meteor Crater in Arizona, a significant geological feature created by a meteorite impact 50,000 years ago. The crater, with its unique squared-off shape and extensive debris field, offers insights into the violent forces that shape planetary surfaces. Credit: Contains modified Copernicus Sentinel data (2024), processed by ESA

The Meteor Crater in Arizona, formed by a meteorite impact 50,000 years ago, provides valuable insights into the geological processes of planetary bodies. Preserved by its desert climate, the crater is a key site for studying impact craters.

For Asteroid Day (June 30), the Copernicus Sentinel-2 mission takes us over the Meteor Crater, also known as the Barringer Meteorite Crater.

Formation of the Crater

Around 50,000 years ago, an iron-nickel meteorite, estimated to be 30-50 m (100-165 feet) wide, smashed into North America and left a massive hole in what is today known as Arizona. The violent impact created a bowl-shaped hole of over 1200 m (4000 feet) across and 180 m (600 feet) deep in what was once a flat, rocky plain.

During its formation, millions of tonnes of limestone and sandstone were blasted out of the crater, covering the ground for over a kilometer in every direction with a blanket of debris. Large blocks of limestone, the size of small houses, were thrown onto the rim.

Crater’s Unique Shape and Context

One of the crater’s main features is its squared-off shape, which is believed to be caused by flaws in the rock which caused it to peel back in four directions upon impact.

The wide perspective of this image shows the crater in context with the surrounding area. The impact occurred during the last ice age, when the plain around it was covered with a forest where mammoths and giant sloths grazed.

Crater Preservation and Importance

Over time, the climate changed and dried. The desert that we see today has helped preserve the crater by limiting its erosion, which makes it an excellent place to learn about the process of impact cratering.

Studying Impact Craters and Asteroid Monitoring

Impact craters are inevitably part of being a rocky planet. They occur on every planetary body in our solar system – no matter the size. By studying impact craters and the meteorites that cause them, we can learn more about the processes and geology that shape our entire solar system.

As part of the global effort to hunt out risky celestial objects such as asteroids and comets, ESA is developing an automated telescope for nightly sky surveys. This telescope is the first in a future network that would completely scan the sky and automatically identify possible new near-Earth objects, or NEOs, for follow-up and later checking by human researchers. The telescope, nicknamed ‘Flyeye’, splits the image into 16 smaller sub-images to expand the field of view, similar to the technique exploited by a fly’s compound eye. Credit: ESA/A. Baker

Over the past two decades, ESA has tracked and analyzed asteroids that travel close to Earth. ESA’s upcoming Flyeye telescopes will survey the sky for these near-Earth objects, using a unique compound eye design to capture wide-field images, which will enhance the detection of potentially hazardous asteroids.

Future Missions and Asteroid Deflection

ESA’s Hera spacecraft, launching later this year, will closely explore asteroids, improve our understanding of these celestial bodies, and help us better prepare for potential future asteroid deflection efforts.